Still, in spite of all obstacles, the inborn poetry of His nature was continually breaking forth through the crevices of His conversation. If His art-feeling seems meager and His insistence upon beauty scant, let us remember that He was forced to spend most of His priceless life in teaching a few of the primary principles of conduct. For the most part He spoke in symbol, in parable, leaving His hearer to point the moral-leaving the truth to be inferred from the beauty. Jesus preached artistically as the true poet always preaches He twined the truth with the beauty. He was moved not only by the beauty of holiness, but also by the holiness of beauty. Jesus carried both ideals in His heart, for He saw the glory of the lilies in the furrow and also the perfidy of the oppressors who walk over graves. Upon Greece came the passion for beauty, upon Palestine the passion for righteousness. No wonder, then, that He was “a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.” Out of the long collision between the is and the ought-to-be, between the world that exists and the world that awaits us in the future, springs that majestic sorrow, that noble reticence, that touches with its shadow all elevated and poetic natures. Jesus, like every great poet, was stung with the pain of genius, the passion for perfection, the yearning for the ideal. Toward these glorious finalities all religion labors and all poesy aspire. This light is the light of the ideal this consecration is the consecration to the service of humanity and this dream is the dream of the social federation of the world.

So Jesus, as the supreme religious genius of the world, carried the vision of the poet. Poetry expresses this beauty in words religion in deeds. To express that beauty is the perpetual aspiration of the poet. Emphasis is mine.Įarth gives us hint and rumor of a divine beauty that broods above us, an ideal splendor that completes the real. His essay “The Poetry of Jesus,” reprinted below, first appeared in the December 1905 issue of The Homiletic Review.

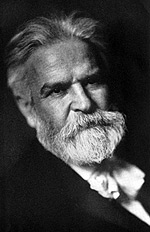

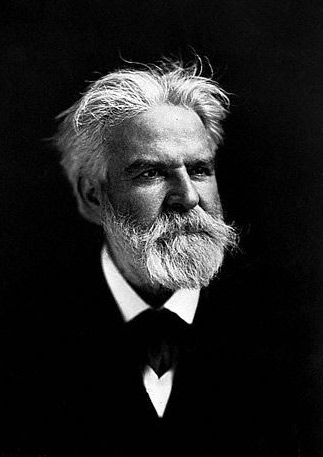

In addressing the issues of his day Markham looked to Jesus, who he considered an embodiment not only of peace, love, and other such virtues but of poetic genius as well. He gained international renown with his poem “The Man with the Hoe,” which, inspired by a Jean-François Millet painting of the same title, protests the plight of the exploited laborer. Edwin Markham (1852–1940) was a popular American literary figure during the first half of the twentieth century whose oeuvre fuses social justice concerns with religious faith.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)